Sundays: Chris Marker and Agnes Varda

From The Left Bank

By Tobi Haslett

Where to begin? Perhaps with an epigraph—no, two—on the pain of beginnings:

"The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Iceland, in 1965. He said that for him it was the image of happiness and also that he had tried several times to link it to other images, but it never worked. He wrote me: one day I'll have to put it all alone at the beginning of a film with a long piece of black leader; if they don't see happiness in the picture, at least they'll see the black. " Sans Soleil, Chris Marker 1983

"I was in Cuba. I brought back jumbled images. To order them, I made this homage, this film... " Salut les cubains, Agnes Varda 1963

For the generation of French filmmakers that bore witness first to the ravages of Nazi occupation and then to the cruel hypocrisies of the Cold War, the world refused to present itself as anything but shattered. Politics, love, even film—everything was a pile of shards to be sifted through and mourned for, perhaps never to be put together again. So we can imagine Agnes Varda sorting her snapshots from Cuba, gawking at revolution and wondering when it will come to France; or we might think of Chris Marker twenty years later, clinging to his precious found footage from Iceland, finding happiness in someone else's blurred, grainy memories, trying to fit it all into a film.

For that generation, the dream of socialism imposed a kind of order upon the disarray of postwar Europe—so the story of Marker and Varda, of Left Bank Cinema, is also the story of the New Left. It is the story of a culture marshaling its forces to combat exploitation and empire; it is the story of young people stupid enough to follow their conscience; it is the story of the wars in Vietnam and Algeria that seemed at last to expose the logic of (neo) colonialism to be not only cruel, but weak and ill-equipped for the coming insurrection, for the brave new world.

But we know how that story ends, and so do the filmmakers whose work we present to you here. This retrospective is an opportunity to reflect not only on two brilliant careers, but also to try and make sense of the roiling mess that was the latter half of the 20th century. And finally, it is an occasion to commemorate Chris Marker's life; he passed away last July, on his 91st birthday.

So we find ourselves acting out our favorite scene from Sans Soleil, in which a Japanese couple burns incense at a temple consecrated to cats. In paying tribute to Chris Marker, we might repeat their prayer for Tora, their cat who was not dead, but had only run away:

"Cat, wherever you are, peace be with you."

2013-04-07 @ 7:00 PM

La Jetée/Remembrance of Things To Come

(Chris Marker, 1962/2003) · La Jetée, Marker's opus, is a sci-fi parable of desire and loss and the pain sustained in memory. Following WWIII, technocrats are hard at work, "hoping to call past and future to the rescue of the present." A man's single hazy memory lets him travel through time, back to the halcyon days–but, in fact, to his demise. Remembrance of Things to Come. is seemingly a work about photographer Denise Bellon, but also a treatise on surrealism and French history.

runtime: 74 min format: 35mm/Digibeta

2013-04-14 @ 7:00 PM

La Pointe Courte

(Agnes Varda, 1955) · Varda's first film revolves around a husband and wife (Philippe Noiret and Silvia Monfort) teetering on the brink of divorce. This orbit is not circular, but elliptical. At times it seems the action moves far away from their marital woes as we become embroiled in some other village drama. But, each time, we are inevitably pulled back into the anguish of our hapless couple, as if to remind us that we are never far from the pain of others.

runtime: 86 min format: 35mm

2013-04-21 @ 7:00 PM

Grin Without A Cat

(Chris Marker, 1978) · An anonymous narrator says, "I'm not among those who saw Potemkin when it first came out; I was too young." What follows is a montage that intercuts scenes from Eisenstein's masterpiece with footage from 1960s student protests. This sprawling epic about the rise of the New Left shares some of Battleship Potemkin's revolutionary convictions, but Marker maintains a skeptical distance throughout. This may be one of the best political films ever made.

runtime: 240 min format: 35mm

2013-04-28 @ 7:00 PM

Cléo de 5 a 7

(Agnes Varda, 1962) · Florence Victoire (Corinne Marchand) is a young pop singer who goes by the stage name "Cléo." Cléo may have stomach cancer. As she waits for her doctor's appointment, she contemplates her own death and the vacuous life she might be leaving behind. Since the film's narrative time is synched up to its running time, we watch the hours as they are really lived—with all the dread, emptiness, and intermittent joy that we have come to expect from real life.

runtime: 90 min format: 35mm

2013-05-05 @ 7:00 PM

Sans Soleil

(Chris Marker, 1983) · A disembodied voice reads letters from Sandor Krasna, an alter—ego of Marker himself. These are tender dispatches from Japan and Guinea-Bissau, "two extreme poles of survival." This essay film is a meditation on culture, memories, and mythology. Krasna resists the condescension one might expect from a European training his gaze on "exotic" continents—rather, what emerges is a frail and forgiving human voice, one in permanent awe of its strange world.

runtime: 100 min format: 35mm

2013-05-12 @ 7:00 PM

Vagabond

(Agnes Varda, 1985) · The film opens with a shot of a woman's dead body lying in a frost-hardened furrow. Who is she? How did she die? We follow the travels of Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire), the vagabond, as she hitchhikes through French wine country and hides from the police. The film is punctuated by documentary-style interviews with characters from her past. In Mona, Varda has found her feminist folk hero, a woman who drinks perhaps too deeply from the chalice of liberation.

runtime: 105 min format: 35mm

2013-05-19 @ 7:00 PM

The Last Bolshevik

(Chris Marker, 1993) · In this documentary, Chris Marker writes six letters to the late Aleksandr Medvedkin, his teacher and friend, who, in the early the Soviet Union, hobbled together a cast and crew that toured Russia's countryside by train. They would shoot short films with the peasants they met, usually finishing quickly enough for the peasants to watch it the next day. The group embodied Marxist practice, yielding the fruits of labor to the laborers themselves.

runtime: 116 min format: DVD

2013-05-26 @ 7:00 PM

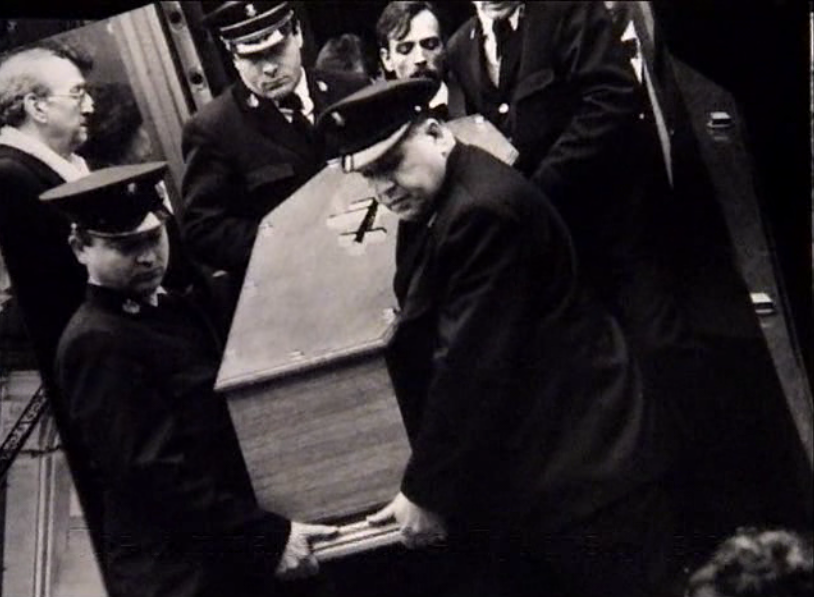

Jacquot de Nantes

(Agnes Varda, 1990) · A moving tribute to Varda's late husband, director Jacques Demy. As a child growing up during the Nazi Occupation, the young Jacquot must retreat into his imagination in order to retain some hope of future happiness. Documentary footage is intercut with fiction, biography speckled with fantasy, and the black-and-white often bursts into color. Varda takes her inspiration from a line of Baudelaire: "I know how to call forth the moments of bliss."

runtime: 118 min format: 35mm

2013-06-02 @ 7:00 PM

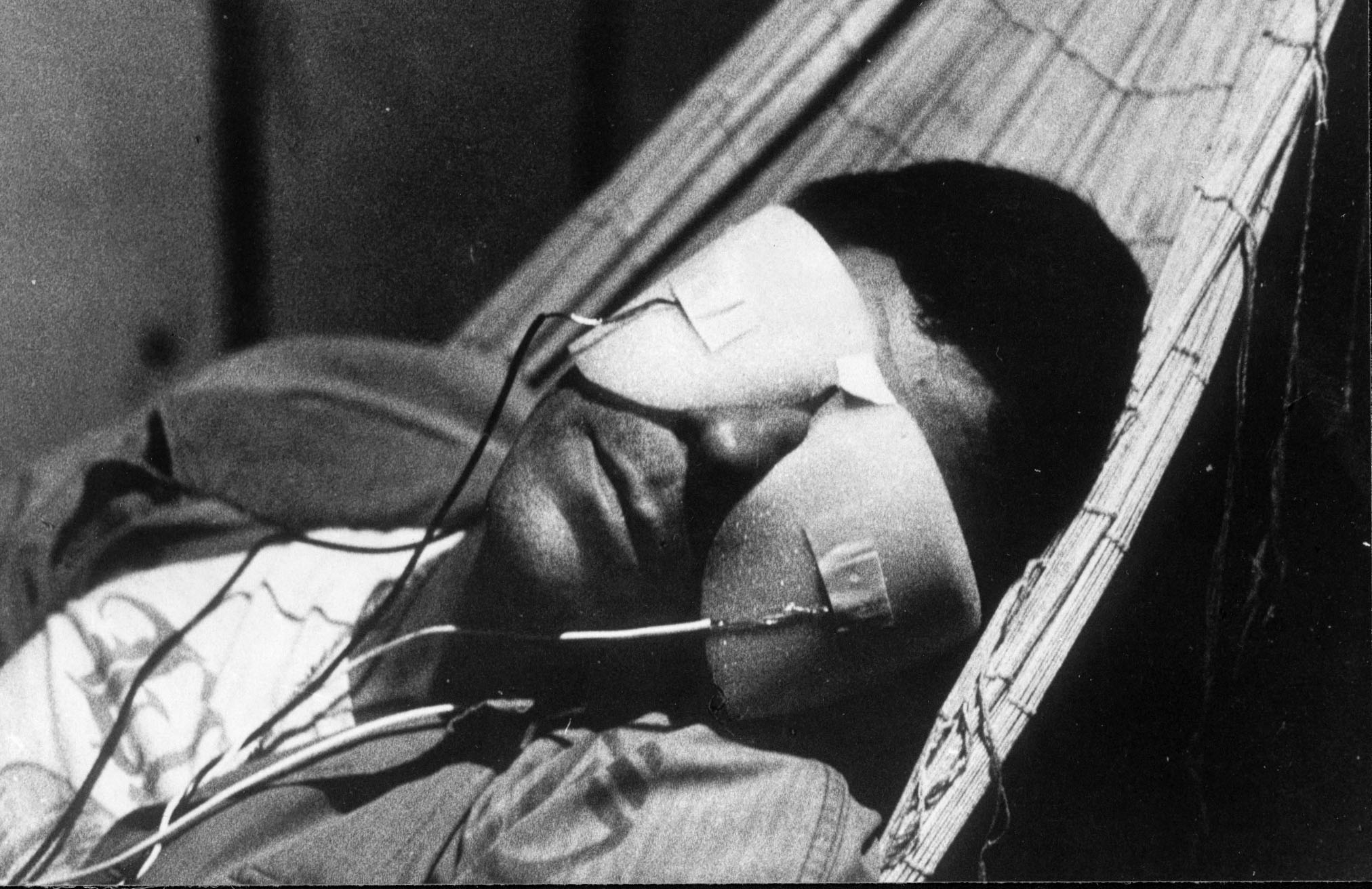

One Day in The Life of Andrei Arsenich

(Chris Marker, 1999) · This eulogy to Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky was originally aired on the French TV series "Cinéastes de notre temps". In it, we view footage of a dying Tarkovsky on the set of his last film, The Sacrifice, and bear witness to his reunion with his son. This portrait is cut with scenes from Tarkovsky's own films, calling to mind what Susan Sontag once wrote: "One cannot use the life to interpret the work. But one can use the work to interpret the life."

runtime: 55 min format: DVD

2013-06-09 @ 7:00 PM

The Gleaners and I

(Agnes Varda, 2000) · Gleaners traditionally collect leftover crops from fields that have already been harvested. Poverty, it seems, never goes out of style. Varda trains a handheld digital camera on all kinds of modern gleaners: France's homeless, nostalgic bumpkins, and psychoanalyst Jean Laplanche. In this wildly popular essay film, gleaning blooms into a metaphor for existence itself, for the gathering of experiences and memories in the hope of survival.

runtime: 82 min format: 35mm